Summer for the Sun Queen

When Gianni Versace was alive, Donatella Versace was happy in his shadow. But after he died and left her daughter, Allegra, the lion’s share of his company, the shadow got darker. It took her till now to get out from under it.

Donatella’s recent collections for women have been embraced by the fashion world—nine years after her brother’s murder, she’s finally being given credit for being a real designer. There will be a few looks for women in this show, too—the precollection, they call it—and a spindly blonde comes out on towering silver stilettos decorated with rhinestones the size of nickels. She walks like an arrogant ostrich for several paces, then wipes out and lands with a brutal thud. Everyone gasps. “Okay. The first fall. We fix,” says Donatella, and pulls out a Marlboro from a pack customized with her initials in Gothic script. “Theez can’t happen on the runway.”

Suddenly, someone brings up shakerados! “Who wants?” says Donatella, and within minutes they appear on a silver tray. Heaven: espresso and ice and sugar and vanilla shaken up and poured in dazzling crystal goblets that sweat in the heat. The second they’ve been consumed, Joseph, Donatella’s Filipino manservant, whisks them away.

All this you expected. The tan skin, the Rapunzel extensions, the chain smoking. The whole freaky, gilded, Jan-from-the-Muppets visual you’ve seen sandwiched between P. Diddy and Madonna in every magazine in the world.

What’s surprising is that Donatella Versace is warm, maternal, an arm-toucher. She pushes a plate at you. “Please. Eat some cake.”

It has long been Donatella’s role to play hostess in the court of Versace. When Gianni, the Sun King, was alive, he was famously regimented—early to bed, early to rise—and utterly uninterested in alcohol, drugs, partying. It was Donatella’s job to be the warm entertainer, the toasted bronze devil proffering temptation: food, leather, gold, and, until recently, cocaine. Gianni was initially in the dark about his sister’s drug use, and later, when it became both obvious and legendary, he frowned upon it, but in truth it was useful to his empire.

At her peak, nobody could top Donatella for all-night, full-on excess—a critical component of eighties mise-en-scène. Everyone knew that there would be coke at the Versace postshow parties (at least after Gianni went to bed), coke backstage (and not just models but supermodels), wildness on their ad shoots (Latin boys in tight white pants, and sometimes tigers). Versace meant whatever you wanted, whenever you wanted it. (Cake! Coke! Shakerados! Who wants?)

Like Princess Diana, who poured tea for aggrieved family members after Gianni Versace’s funeral and was herself killed just six weeks later, being struck down in his prime has served to gild Gianni Versace in myth. Fashion people gush about his talent, museums hold exhibitions of his work, and everyone who knew him adopts a glazed look and a reverential tone when they speak of him. But the Sun King’s brilliance seems, at times, to have fried his sister.

Rumor has hardened into accepted wisdom in the fashion world that Gianni arranged Donatella’s marriage to the male model Paul Beck because he wanted an heir for his throne. It is also widely believed that Gianni’s feelings for his sister’s husband were more than platonic. It is certain, at least, that Gianni had a role far more powerful than uncle in the life of Donatella and Beck’s children, particularly for their daughter, Allegra, whom Gianni called “Little Princess” and to whom he left the majority share of his company.

“My cheeldren were his cheeldren,” says Donatella. “He was always with Allegra. Since she was 9 years old only, she would listen to him, she was going to see museum, she knew all the museum in America, in France, in England, and Gianni loved art. She would sit with him and go through art books, and she knew the art of Picasso ... it was adorable. She was such an amazing, special leetle girl.”

Donatella always knew Allegra would someday hold the controlling stake in Versace: It was, she says, a kind of parental incentive the king created for her. “ ‘I want to leave everything to your daughter because I want to make sure you take care of her so well.’ This is what he was telling me. ‘Do such a good job, because everything goes to your daughter.’ ” She did not question the king’s decree: L’Etat, c’est Gianni. “Gianni was amazing,” Donatella says ruefully. “He really was amazing. But if he wasn’t like that, he wouldn’t have reached what he reached in such a short time.”

“He was my best friend. I really loved him. I couldn’t find a reason why he was killed. This was a horrible murder, and this company he created, they were looking at me like, ‘What’s she gonna do? The king is dead.’ ”

It would have been a failure too epic to contemplate; the opera would have become too tragic to sit through. “The thing that killed me the most was to show this strong façade in front of everybody because I wasn’t strong at all. I was going home and crying tears. I also had my cheeldren to be strong for ... Why Uncle Gianni die? Why? Why? Why? Why? It was a lot. It was a lot of things together, my marriage falling apart at the same time.” She doesn’t talk about what happened with Beck except to say, “I have been living with a lot of pain in my life: private problems, family problems. I found an easy way to numb everything ... drugs.”

“I like beauty,” Donatella says the following evening, over a plate of prosciutto and a little pile of melon balls. “Hair that moves. I don’t like anything stiff.” She is talking with her team about the way she wants the precollection styled on the runway—everyone eats dinner together, family-style, in a room on the ground floor of the palazzo on Via Gesú.

“Better,” she replies, and everyone laughs.

If you were to go by the Ralph Lauren headquarters, it is unlikely you would find Ralph himself sitting down to supper with his staff, but this is Italy. Donatella likes to see people eat, she likes things familial, she likes to be intimate with the people who work for her. “Dinner was always in her suite, she tells you where to sit, she makes sure everybody eats,” says Jason Weisenfeld wistfully. “We were always very well taken care of.”

“It’s like Disneyland, yes?” says Donatella.

Santo is very grave. “I like very much Dubai seven or eight years ago, but now it’s a very crazy place.” They will bring in barrels of fish to put in the lagoons and ponds.

“Very natural,” says Donatella with a small snort. “Similar to Las Vegas.”

“Las Vegas is not real. Dubai is real,” Santo says.

“I want to go there next week!” says Bill Mullen.

“Pfoof,” says Donatella, and exhales a plume of smoke.

Gianni Versace left 30 percent of his company to Santo, 20 percent to Donatella, and 50 percent to Allegra, who will turn 20 this weekend and is studying drama at Brown University. And so it is that Donatella Versace finds herself from time to time in Providence, Rhode Island.

“I couldn’t picture me in Providence, let alone her!” says Mullen, who attended Brown himself.

It’s a funny thing about coke, how it’s always the people who are already kind of manic who are the most drawn to it, like they want to see how amped-up they can possibly get without their heads’ blowing off their bodies. (Don’t they ever want to unwind?) There is something a little cokey—but very nontoxic—about Donatella’s vibe even now that she’s sober. She speaks very quickly. She laughs easily. She paces. She is little and coiled: a tight, tiny spring.

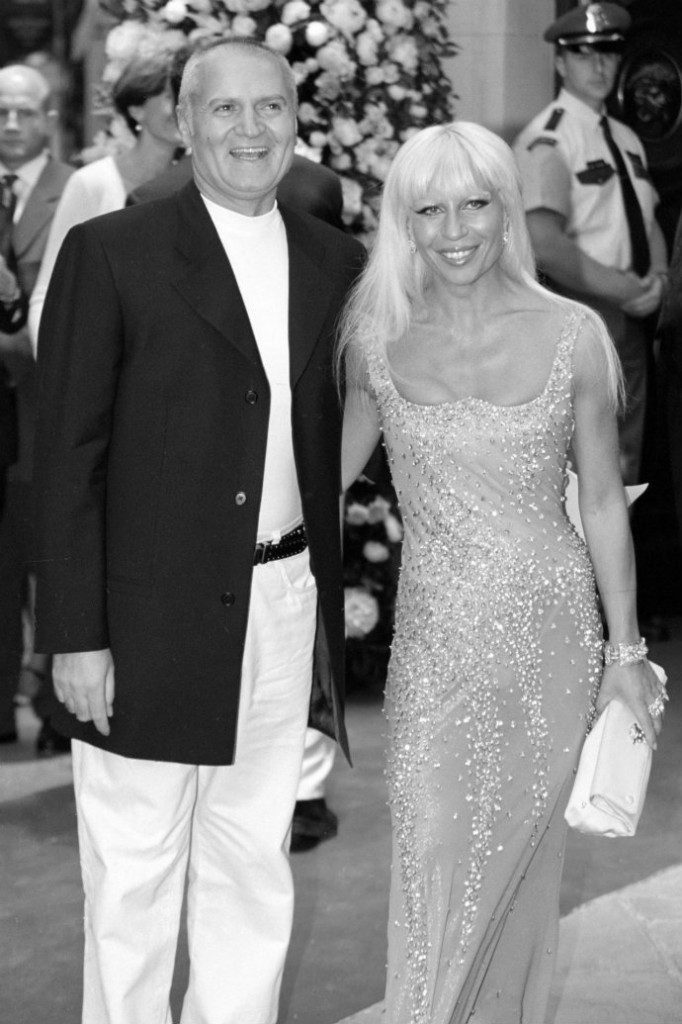

A photographer and his assistants are waiting upstairs for Donatella to come out and have her photo taken. She is running late, and she has allotted very little time for them anyway, and everyone is edgy but awed by the surroundings. These were once the king’s quarters. There are giant bowls of pungent lilies; a phalanx of marble heads carved before the birth of Christ; a collection of priceless antique globes; and a series of black-and-white photographs of Gianni, Donatella, and Santo with their relatives in Calabria, the Southern Italian town of their birth. Gianni sits grinning in front, Santo stands smiling behind him, Donatella looks very young, very modest, and very distant. Her nose looks different.

That was then. Now Donatella must run the kingdom until the Little Princess is ready, and she has a show to put on and a collection to edit and a photo to pose for. But the makeup and the hair take so much time, and they are so crucial, she knows. Nobody wants to see just some person; she cannot appear before her subjects out of full regalia. So she keeps the photographer waiting as someone works on the eyes and someone works on the tresses, and she sends Joseph out with yet more cakes.

Donatella emerges in all black. She always kept a room here as a place to stay when they were working late. “The last two years of Gianni’s life,” says Donatella, “I was going up into his apartment, showing him the work, getting the approval from him, but I ran the company because he wasn’t showing himself. It was like a year and a half I did everything.” On her walls there are two pieces by Julian Schnabel made from ceramic shards, a portrait of Gianni, and another of Allegra and Daniel. “The other way was more convenient for me, when I was next to Gianni, because Gianni was the one with all the responsibility, taking all the criticism. It was a more comfortable position.” She laughs. “Even if he said what was wrong was my fault, that was okay.”“It starts as a celebration,” says Donatella. “You don’t do drugs because they aren’t fun. They’re a lot of fun. But the celebration gets too often celebrated.”

The next evening at the New York Times party in the garden of the Hotel Bulgari, people are gushing sweat and drinking champagne. Paul Beck, Donatella’s ex-husband, is in a gray shirt soaked through the armpits and the front of the chest. He still works for Versace, as he has for some twenty years, and he is circulating among the fashion press while Donatella prepares for the men’s-show rehearsal. He says hello to Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, who both wear their company’s name on a gold plate on the tail pocket of their jeans. He exchanges greetings with Pharrell Williams, who is in pink sneakers. “He played at my daughter’s birthday party,” Beck explains—Allegra’s 18th, which was just before Donatella went into rehab.

Beck goes on to a party Vogue is throwing, at which Santo Versace is already chatting with Rupert Everett, who wears head-to-toe gingham. He makes an appearance at a glittering GQ soiree held in Milan’s Humanitaria. Gardenias float in little candlelit pools, and everyone is getting drunk and waiting for Pharrell to perform. Finally, Beck heads to the Milan Stock Exchange, where Donatella is having her rehearsal.