![Image result for Black Actors/Actresses on NBC Passions]()

Well before primetime shows like Empire, daytime TV was the place where diversity and complexity learned to coexist.I’m a fourth-generation soap watcher who got hooked on the shows the way a lot of fans do: spending summers watching TV alongside an older relative during school breaks.

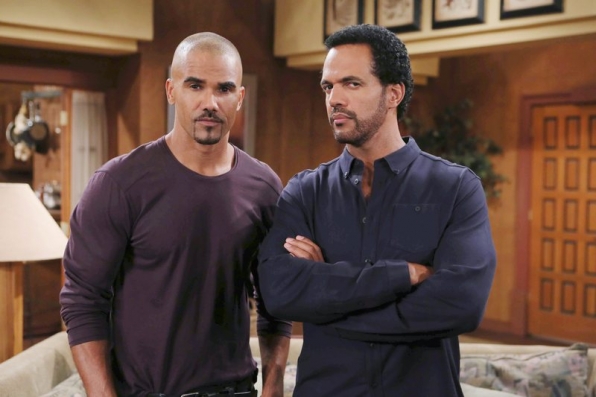

In her later years, my great-grandmother kept two TVs and two VCRs in her apartment—one to tape the ABC soaps, and the other for the CBS soaps, of which her all-time favorite was The Young and the Restless. Y&R, its nickname in the soap world, was also my grandmother’s favorite and my mother’s, so naturally it became mine.

By far, Y&R was the easiest to keep up with: You could tune out for a week without missing anything crucial to the overarching story, and it was accessible because, unlike some other programs, the same actors stayed in the same roles for years.

In black households, we are taught to root for the black person on TV.

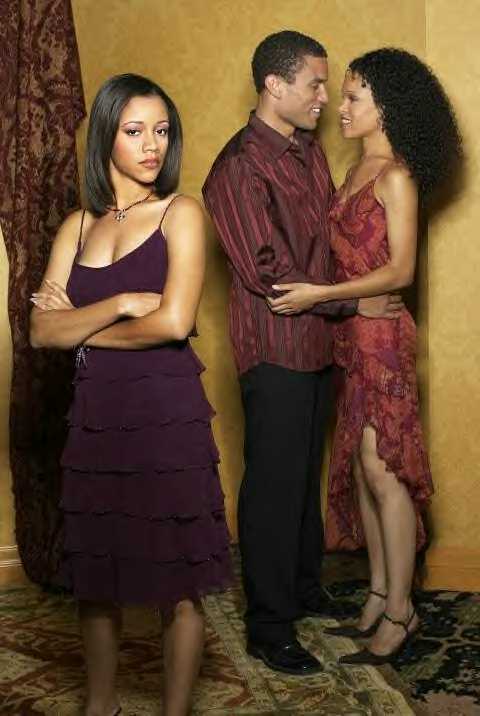

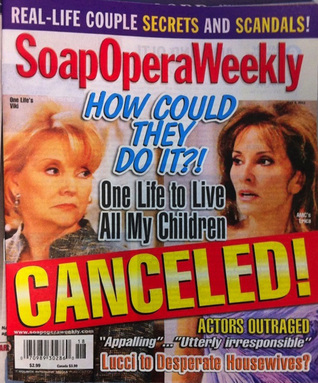

But another big reason Y&R was beloved in my family was its black characters, who flourished in the 80s and 90s: They began as background figures, but slowly evolved into pillars of their fictional community. Born the year The Cosby Show premiered, I grew up watching 227, Amen, Family Matters, and A Different World not knowing how hard it was to integrate TV; for me, black folks were already there. There was a point in my childhood when I knew Drucilla, Olivia, Neil, Nathan, and Mamie, Y&R’s powerhouse stable of 90s black characters, better than some of my own cousins.So it's interesting to see primetime television and streaming services like Netflix being heralded for ushering in a new age of black television, as if we were never allowed to be ourselves onscreen before. But daytime, before primetime, provided valuable space for black characters to be layered—and for viewers, black and otherwise, to appreciate their complexity. Every time I see these new-school characters, I remind myself of where I’ve seen them before. Well before Annalise Keating of How to Get Away With Murder was a tough, black woman lawyer with a complicated interracial marriage, there was Jessica Griffin on As the World Turns, an attorney who faced scrutiny before marrying her white fiance, Duncan. It wasn’t all that shocking when Mary Jane Paul on BET's Being Mary Jane stole her boyfriend’s sperm if you'd already seen Virginia Harrison carrying around semen from a sperm bank–with a turkey baster!–to impregnate one of her rivals on Sunset Beach.In many ways, daytime soaps preceded the kinds of diverse approaches to storytelling now championed by Shonda Rhimes dramas. But their contributions weren’t valued then, and they’re still largely ignored today. Black soap actors have rarely won mainstream recognition for their portrayals, and many of their characters’ storylines are lost to history as the genre's popularity continues to wane among viewers.

"At least on the soap, black characters are role models for middle-class people—nice, normal people." ![]()

Little has been written on the subject of diversity in daytime. But in the genre's earliest years, some soap operas embraced unusual nuance that paved the way for a wider range of characters. Irna Phillips, who created soaps including Guiding Light, As The World Turns, and Another World, told a talk show host shortly before her death in 1973 that “as a writer, there isn’t a black or a white, or a square or a bad joke … We’re all brave. None of us are either black or white, or bad or good.” Phillips wasn’t referring to race: Many of her soaps only featured blacks in supporting or recurring roles well into the 1970s.

But she did champion a three-dimensional style of TV storytelling, giving the genre freedom for characters—male and female, husbands and their wives—to be accepted for their flaws. This, by extension, allowed for future soap writers to wean audiences onto equally flawed characters of color. As absurd as the genre can be, early soaps frequently focused on serious, everyday worries: The origins of Guiding Light trace back to a clergyman who fretted about what kind of messages to deliver to his flock, and the 1960s delved deeper into topics like the Vietnam War and abortion.Not that it was easy. In 1968, daytime’s first black heroine was Carla Benari on One Life To Live, the ABC soap created by Agnes Nixon, who was a friend of Phillips. Played by actress Ellen Holly, Carla was actually “Clara,” a housekeeper’s light-skinned daughter passing for white to avoid the discrimination of the day.